Hotels and Motels vs. AirBnB

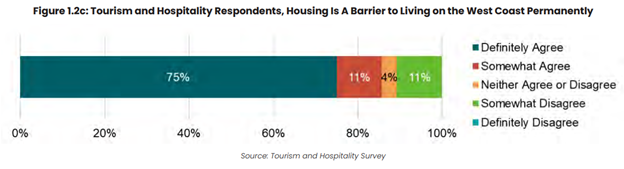

Over the past decade, there has been an exponential boom in online short-term rental (STR) platforms like Airbnb. Ucluelet has seen an explosion of STR’s in our residential neighbourhoods. Uncontrolled, we could see the equivalent of another eight Blackrock Hotels develop in Ucluelet’s existing residential properties, representing about a thousand units and thousands of additional tourists. There is a great deal of research available on the impacts of Airbnb expansion on long-term housing availability, housing costs, and amount of non-resident property owners. One area which doesn’t receive the same research attention is the impact of increasing Airbnb’s on local job markets, particularly traditional tourist accommodation jobs, such as hotels.

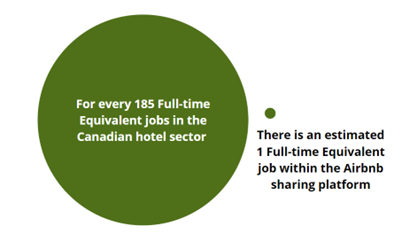

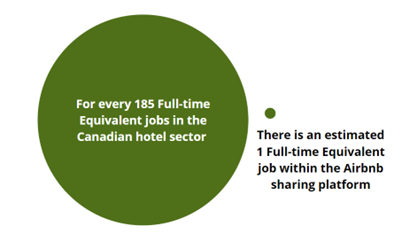

Studies show that expansion of Airbnb and other hyper lean short-term rental platforms directly results in reduced revenue share for hotels and traditional tourist accommodations. This shift can negatively impact employment since some of the labour of maintaining short-term rentals is done by property owners or outsourced to a third-party. Traditional hotels are a more labour-intensive source of employment than Airbnb, and often include management positions, front desk, housekeeping, room attendants, laundry, financial services, guest services, food services, sales and marketing, maintenance and operations, security, and housekeeping. Jobs associated with Airbnb’s and other short-term vacation rentals require very few employees to function, so as these accommodations expand, they can result in an overall loss of employment positions.

Hotel workers have access to labour rights such as statutory holidays, annual leave, medical coverage, and sick leave. Airbnb hosts, by comparison, are not employees of the company but are usually classified as self-employed and may outsource hosting or cleaning requirements, which means platforms like Airbnb can operate by collecting fees on their services while not offering hosts and associated workers the labour protections offered by an employee status. Because of the informal nature of a lot of short-term vacation rental platforms, it is hard to collect data to accurately compare job creation for traditional tourist accommodation and platforms like Airbnb. The research that has been done shows that hotels generate significantly more employment positions than Airbnb’s. In Canada, the hotel sector supports a much higher number of full-time equivalent jobs.

Airbnb and other short-term rental platforms can be a beneficial and flexible way for property owners to generate increased revenue and provide tourist accommodations. These hyper lean platforms create savings by outsourcing tradition work like advertising and booking management plus they allow for the easy remote operation of tourist accommodations so that running a B&B from outside the community is easy and hard to police. These easy and outsourced operation models may benefit individual property owners but can have a devastating long term effect to the sustainability and livability of the community. Research shows that those benefitting most are disproportionately wealthy households, with even higher benefit shares going to non-resident and commercial owners. The loss of more secure, traditional tourist accommodation jobs as hyper lean accommodation platforms expand can be a difficult scenario for communities to navigate to ensure sustainable, long-term labour markets.

Sources & Further Reading

Rivens, J. (2019). The economic costs and benefits of Airbnb. Economic Policy Institute. Available at https://www.epi.org/publication/the-economic-costs-and-benefits-of-airbnb-no-reason-for-local-policymakers-to-let-airbnb-bypass-tax-or-regulatory-obligations/.

Lee, M. (2016). Getting Serious About Affordable Housing: Towards a Plan for Metro Vancouver. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Available at https://policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/BC%20Office/2016/05/CCPA-BC-Affordable-Housing.pdf.

Gold, A. E. (2019). Community consequences of Airbnb. Wash. L. Rev., 94, 1577. Available at https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5086&context=wlr.

Barron, K., Kung, E., & Proserpio, D. (2021). The effect of home-sharing on house prices and rents: Evidence from Airbnb. Marketing Science, 40(1), 23-47. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3006832.

Wachsmuth, D. (2021). Short-term rentals in Canada: The first comprehensive overview. Canadian Journal of Urban Research (30). Available at http://upgo.lab.mcgill.ca/publication/short-term-rentals-in-canada/.

Shirley Nieuwland & Rianne van Melik (2020). Regulating Airbnb: how cities deal with perceived negative externalities of short-term rentals, Current Issues in Tourism, 23:7, 811-825, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13683500.2018.1504899.

Hohol, F. & Godfrey, R (2017). An Overview of AirBnb and the hotel sector in Canada: A focus on hosts with multiple units. CBRE Limited Valuation & Advisory Services. Available at http://new.hotelassociation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Full-Report.pdf.

Fang, Bin & Ye, Qiang & Law, Rob (2016). "Effect of sharing economy on tourism industry employment," Annals of Tourism Research, Elsevier, vol. 57(C), pages 264-267. https://www.cabdirect.org/cabdirect/abstract/20163128328.

Zervas, G., Proserpio, D., & Byers, J. W. (2017). The rise of the sharing economy: Estimating the impact of Airbnb on the hotel industry. Journal of marketing research, 54(5), 687-705. https://people.bu.edu/zg/publications/airbnb.pdf.

Dogru, T., Mody, M., & Suess, C. (2019). Adding evidence to the debate: Quantifying Airbnb's disruptive impact on ten key hotel markets. Tourism Management, 72, 27-38. https://open.bu.edu/handle/2144/40257.

Tremblay-Huet, S. (2018). Making Sense of the Public Discourse on Airbnb and Labour: What about Labour Rights? In D. McKee, F. Makela, & T. Scassa (Eds.), Law and the “Sharing Economy”: Regulating Online Market Platforms (pp. 393–420). University of Ottawa Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv5vdczv.16

Henderson, M. (2020). Short-term rentals, long term consequences: regulation and enforcement of vacation rentals in small Canadian communities. Ryerson University. Available at https://rshare.library.ryerson.ca/articles/thesis/Short-term_rentals_long_term_consequences_regulation_and_enforcement_of_vacation_rentals_in_small_Canadian_communities/17326163/1/files/31993349.pdf